Toxic Town?

They won their fight for justice and now a group of mothers who took on Corby Borough Council in the 2000s are hoping a big budget Netflix drama will raise the dangerous issue of toxic waste once more

By Sarah Ward

Before you read this article, if you are new to NN Journal sign up for our free, independent news about Northants.

When she was pregnant with her first child Shelby, Tracey Taylor, worked at the Euromax factory on the Earlstrees industrial estate in Corby. Joining the firm straight from finishing school in 1989, by the time of her pregnancy in 1996, a red dust had been hanging in the air for a couple of years.

Tracey says:

“We noticed these sand storms more and more. On days when it was really hot - it would just fly over. It was coming off the trucks as they were driving around. None of them were covered. When it was wet it was like you were going through a slurry pit.”

Tracey’s office desk was covered in the red dust, which would leave a mark when a coffee cup was moved.

“Because it looked like mud and we were on an industrial estate, you just assumed it was mud dust. You don’t expect it to be toxic waste. Our lunches were uncovered. We were eating and drinking it.”1

One day on a regular lunchtime walk to the nearby ponds, Tracey saw barrels stamped with skull and cross bones, floating in the water. There were dead birds and fish nearby.

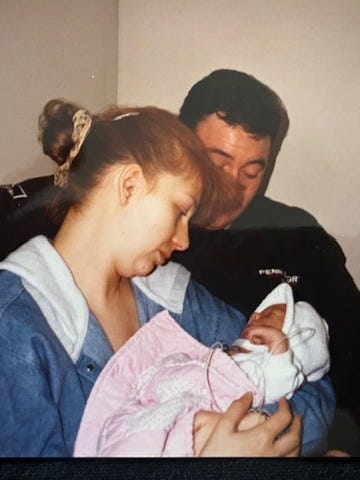

In mid April 1996, Tracey gave birth to Shelby at Kettering General Hospital. Her heart was not fully formed and one ear was deformed. She was moved to John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford for specialist treatment, but tragically died three days later.

Working at Euramax with Tracey was Peter Ford, whose wife Susan was also pregnant with their second son Connor. He was born four months after Shelby and had no fingers on his left hand.

Less than two miles away from where Tracey and Peter worked, in Rowlatt Road, a pregnant Maggie Mahon, had to beat her husband Derek’s work clothing against the back wall of their house, when he came home from his daily shifts as one of the truck drivers moving the soil from the contaminated land.

In July 1997 her second child Sam was born. He was born with one foot turned inwards, known as a club foot.

The dust was being caused by the clean up operation of former steel works land, but the expectant mothers, like the majority of the town, did not know that the sludge being transported around the town throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, in open trucks, was toxic and harmful to their health. It contained a cocktail of toxic ingredients such as cadmium, lead and arsenic, the by-product produced in the decades of steel making that had built and employed Corby.

After the steelworks closed in 1980, Corby Borough Council took on the biggest land reclamation project in Europe, acquiring 200 acres of land from British Steel and giving the main contract to Weldon Plant to clean up the contaminated land that was scattered across the North East of the town, in order to build new employment sites to shorten the growing job queues. But the clean up was mismanaged, safety procedures such as covering the trucks were not followed, some waste was dumped incorrectly and there were concerns about how the contract was being handled. After a tip off, police raided the council offices in 1996, but three years later the CPS decided there was not enough evidence for a prosecution.

But as was proved at the high court in 2009, the toxins disturbed by the clean up of the contaminated land caused some children born between 1989 and 1996 to suffer harm while in the womb. Corby Council admitted that mistakes had been made.

TV drama and BBC podcast

Today some of the mothers will lose their relative anonymity, as their stories have been fictionalised for a new Netflix drama Toxic Town. Starring big names such as Doctor Who’s Jodie Whittaker, Robert Carlyle and Corby’s own Downtown Abbey star Brendan Coyle, the four-part drama written by Jack Thorne, tells the story from before the children were born right through to their victorious court case in 2009. All of the mothers featured hope the programme will raise the health issue once more.

Tracey, who has three sons, said:

“I think the council had always tried to put across that us mothers were looking into things we shouldn’t have been. Even when they did the settlement, Chris Mallender [Corby council’s chief executive] said ‘this payment equates to £5 per household’. I think they tried to make it that us mothers were clutching at straws. “Quite a lot of us were called gold diggers and that we were in it for the money. 2

“That is why when Netflix approached, we said, ‘Yes we will do it.

“We don’t want fame, we don’t want glory, we don’t want anything. It’s the fact that there are more people who have been affected by this than they realise. This may highlight it and like us, people may sit there and put two and two together.

“And I would hate to pick the paper up in my lifetime and find history repeats itself.”

Maggie Mahon, did not share her family’s story in the media at the time for personal reasons and says their going public now is in part due to their earlier silence.

She said:

“We did think ‘We should have spoken out more’. We felt a bit victimised with the council saying ‘everyone’s council tax is going to go up’ so we felt alot of people were against us. And thought it would be nice if people knew what really happened.”

And next week a BBC local podcast will run an eight episode series called the Toxic Waste Scandal. It will be available on BBC Sounds and will be narrated by George Taylor, one of the children born with a birth defect.

How the wrongdoing first came to light

In 1999 Susan McIntyre received a knock on the door from Graham Hind, a reporter at The Times. He had been tipped off by people close to the local authority who said the clean up of the former British Steel sites was not being done safely and could be the cause of some children being born with limb deformities.

His initial story, which featured Susan and two other mothers, was then carried forward by the local media, and as more stories were written and aired in local TV and radio, more families started to come forward and approach the solicitor Des Collins who had taken on the case. During this time many of the children were having numerous painful operations to try and correct their birth defects, with many trips to hospital and some suffered bullying and taunts from other children.

Tracey Taylor became part of the legal action after catching a glimpse of the local TV news. A doctor at John Radcliffe had asked her after Shelby’s birth whether she had ever been exposed to toxic waste, a question at the time which seemed ridiculous, but when she saw the report and read that evening’s Corby Evening Telegraph, things became clear.

She said:

“Straight away, when I heard the words toxic waste, I was like, ‘hang on a minute.’ Oxford has asked if we had been exposed to toxic waste, and the more I thought about it, and following the lorries, all the pieces just fell into place quite quickly, that evening. It was just too much of a coincidence. I said to my mum ‘I’ve got so much running around in my head. I think that’s what has happened to Shelby.’”

As the local media continued to cover the plight of the families and their legal team’s battle for information from the council, the numbers of families grew to more than 40, although in the end only 18 families were part of the case.

Maggie’s son Sam was one of the final claimant group and the Mahon family joined the case after reading about it in the local paper.

Maggie says:

“When I read the newspaper reports about the reclamation, I said to Derek, ‘Did you work there? And he was like, ‘Yes I’ve worked on and off of those sites for years. They had shared work vans, which I would go in as well. I did not know what they were moving, maybe that was ignorance on both of our parts.”

Maggie continues:

“I was angry and I thought, if this has happened I am going to fight for my child.

“From a week old, it was constant treatments, splints, bars, operations. It was ongoing. But I brought him up to be positive and not to dwell on it.”

Maggie thinks that because of its industrial past, people in Corby did not really question the mud on the roads.

She said:

“We had lived with the pollution of the steelworks, my mum used to have to go and get the nappies off the line, as there was black dust.”

Between the first Times story in 1999 and the court case in 2000s the legal team, aided by drop offs of mystery documents from those with links to the authority and commissioning their own experts to debunk local health reports, built their case, which would lead the high court judge to decide there was a link between the toxins and the birth defects. It was a landmark case.

As Shelby had died, her claim was not taken forward with the other children, who had suffered limb birth defects, although Tracey did take to the stand at the high court and give crucial evidence about the dust that she was exposed to during her working day.

She says she does not have any bad feelings about not receiving compensation, as she takes comfort in the fact that Shelby’s short life has helped other children secure justice. Herself and her husband Mark, never received a written apology from Corby Borough Council.

Is the town still suffering the health impacts?

The three mums featured in the drama that NN Journal has spoken to feel strongly the mismanaged clean up has had other health impacts on Corby’s community. They have had health issues in their immediate family and know of friends and former colleagues who worked in the area who have suffered chronic illnesses and cancers.

Tracey says:

“Nobody knows where the toxic waste has been dumped, whether it was containment cells done properly? How long do they last? The documentation is missing. If anybody wants to build on that or dig it up, is anybody going to say, ‘hang on a minute’. We have to look into this because there are containment cells with toxic waste in.

“All of us mums have said ‘It is a sitting time bomb. Unless somebody acts now and things are looked at and documented, it is going to repeat itself’.

“It is still a big jigsaw puzzle and all the pieces need to come together. Stuff needs to be put in place to stop this happening in the future.”

Writer Jack Thorne told NN Journal, he hopes Toxic Town will “encourage councils to think twice about some of their methods and how to answer the need for growth versus the need to keep people healthy.”

Asked why he thinks it takes so long for wronged groups to get justice in the England, he said:

“I think that what happened in the 1980s in terms of the destruction of the unions, the destruction of solidarity is something we are still paying the price for today and what happened was a lot of people were left in penury and survival at any price became the code word and that London was allowed to grow and everything else was sort of allowed to sink. And it was a case of, if you are living in those areas you are lucky to have a job.

“They [the former borough council] were aware there was red tape they needed to push out of the way and perhaps not enough consideration was given to what that red tape was there for.”

NN Journal asked North Northamptonshire Council (which replaced the former council in 2001) whether it is currently monitoring or investigating any of the former steelworks land and received this reply:

In 2001, Officers from the former Corby Borough Council carried out a review all of all sites in Corby that could be identified as potentially contaminated land, in accordance with the legislative requirements at the time, and risk rated them to assess those which could have a negative impact on human health, using the source-pathway-receptor pollutant linkage model. The resulting ‘Programme for Inspection and Arrangements for Detailed Inspections’ was detailed in chapter 7 of the subsequently produced Contaminated Land Strategy, which has now been superseded by the North Northamptonshire Contaminated land strategy, available on the Councils website. Those areas that required remediation, under Part IIa of the Environmental Protection Act 1990, were remediated. The funding for this remediation, provided by DEFRA is no longer available to Local Authorities, so remediation of sites is now mainly through the planning process.

When a planning application is received, Officers of Environmental Protection within Environmental Health are consulted and they will review the historic maps of the site to ascertain the likelihood of any previous potentially contaminative use of the site, as well as considering the proposed end use (commercial/residential etc) to make a decision as to whether a contaminated land investigation is required. The requirements for such investigations are contained in the Environment Agency Guidance Documents Land contamination risk management.

North Northamptonshire Council is also the holder of an Environmental Permit for a former landfill site based within the former steelworks site. Compliance with the conditions of the permit are regulated by the Environment Agency – gas and water sampling takes place on a yearly basis as part of the requirements of the permit.

The legal definition of contaminated land is set out in the Environmental Protection Act 1990 and the likelihood of a site meeting any of the criteria is low. Very few sites have been determined as contaminated land nationally and none of these sites are in Corby.

Each sovereign authority has identified a number of potentially contaminated sites based on an inspection of the district. This information is commercially confidential and incomplete. Any land identified as potentially contaminated does not mean that contamination is actually present. The birth defects case was a private, civil action taken by individuals against the former Corby Borough Council. This was not an action brought under the contaminated land regime as per Part IIa of the Environmental Protection Act 1990.

Today NN Journal is starting a new investigation into the impacts of the contaminated land clean up.

And we need the help of readers and those who have lived and worked in Corby.

If you were involved in the legal action but did not become part of the final claimant group; worked in the reclamation or for the former Corby Borough Council; were employed in in the local health sector; have any information, reports or concerns, please get in touch at sarahward@nnjournal.co.uk or by calling 07887 500545.

All information will be treated in confidence.

There is no suggestion that Euramax has done anything wrong.

The compensation payments were covered by non-disclosure agreements and Maggie Mahon says there were nowhere near as large as people believed.

With the TV drama shedding light on the attempts by the council to cover up the truth, it is truly shocking to see the extent of the impact on our community. The health implications of these toxins, especially on our children, are deeply concerning.

The high levels of cancer cases among babies, children, and young adults in Corby are alarming and point to the long-lasting effects of exposure to harmful substances. It is crucial for us to be aware of these issues and to demand accountability from those responsible. As a community, we need to come together to address this issue and ensure the well-being of our residents. It is time to stand up and take action for a healthier and safer environment for all.

Another scandal is the inaction of Northants County Council and then West Northants Council regarding air pollution. They declared seven Air Quality Management Areas between 2003 and 2009 because the air pollution was above legal limits. They were legally required to publish an action plan for each withing 18 months of declaration, but they did nothing. During the last two decades of inaction over 2,000 people have died in Northampton from air pollution. When will those responsible be brought to justice? How would we get action taken?