Special report: ‘There’s another one from Corby’

Rare conditions and cancers, childhood’s blighted by pain. Families want answers about whether their health conditions have been caused by Corby’s mishandled toxic waste clean up.

By Sarah Ward

If you’re new to NN Journal sign up for our regular, free news here

Since airing earlier this year, the Netflix show Toxic Town has shaken Corby.

A dramatised account of a group of families’ real-life court battle to prove the reclamation of contaminated steelworks land caused their children’s birth defects, in the months since its airing, it has got many in the town talking and considering their own situations.

The original court case centred around children who had birth defects, but there is now a wider concern about what other health impacts this ‘toxic soup’ that had hung over the town during the clean up in the 1980s and 1990s has possibly caused.

There are concerns about cancers, rare conditions and heart problems.

Over the past few months NN Journal has spoken to many Corby residents who have started to question whether their illness may be connected to the town’s toxic waste.

In all of the cases reported here, there is a link between the person and the reclamation sites, either by their parents living close to the area when they were born, or working in the nearby industrial estates.

Rare conditions and cancers

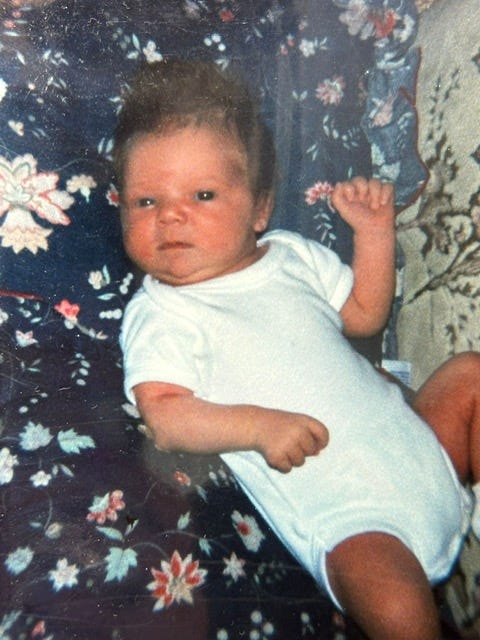

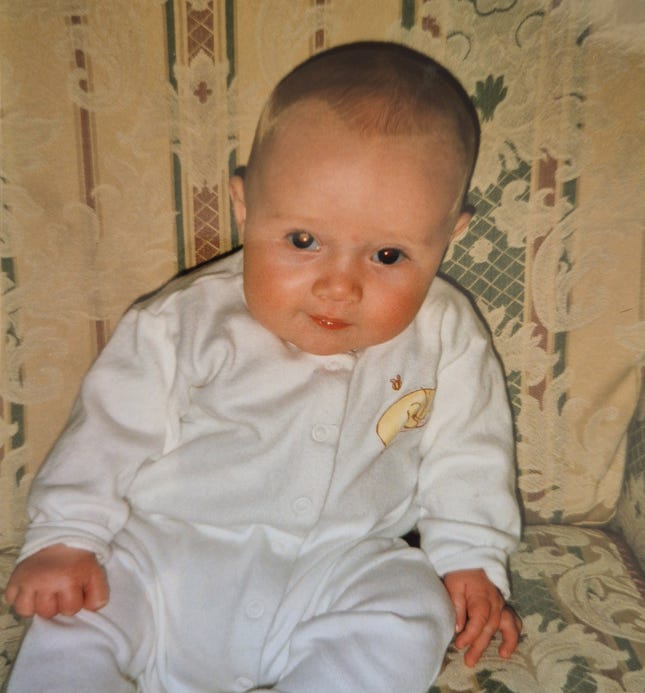

Sarah McLeod was born in 1989 with her heart on the wrong side. All her major organs are also mirrored, a rare congenital condition called dextrocarida situs inverus totalis. The causes of the condition are unknown, although believed to be due to genetic changes during foetal development. Her dad was a steelworker and her mum worked in factories on the Earlstrees industrial estate.

Her condition was not picked up at birth.

She says:

“I kept getting chest infections so my mum and dad had me back and forth to the doctors, but they never had an answer, they just kept saying ‘it’s viral’. Then I had shingles when I was four, went to the doctors, and they said ‘I think there is something going on with the heart’. So they did a chest x-ray, I got sent to the heart doctor and found out I had this condition.”

At 12 she developed a heart murmur and has had pneumonia on two occasions.

She says:

“No-one knows why I have it. As a teenager I just got on with it, but when I tell people they don’t believe it and have to touch my chest.

“But the older I have become, I think ‘it is strange’. I’ve never met anyone else who has it.

“No one in my family has it - my two brothers were born fine, it has not been passed onto my three children.

“When I’ve looked into it in the past, mothers who were anti-depressants and air pollution have been mentioned.

“I used to say to my mum, ‘What did you do when you were pregnant with me?’ and she said ‘ nothing’, she can’t even swallow a paracetamol.”

Sarah knew about the court case in the 1990s, as she went to Irish dance school with Simone Atkinson, one of the original claimants, they were both born in the same year.

She says:

“Because I do not have an external deformity, mine is internal, I did not connect it. But when I watched the BBC documentary and they mentioned Shelby-Anne (Shelby is the child of Tracey and Mark Taylor and died at just four days old due to her heart not being fully formed) I just thought ‘that’s strange’. As it was to do with her heart. I thought it was just to do with hand and feet deformities. Nobody spoke about anything to do with internal organs.

“That’s why it made me wonder. I thought, ‘I was born in that time period. My dad worked for British Steel’. None of my family have got this and it is rare. There is no explanation as to why it has happened.”

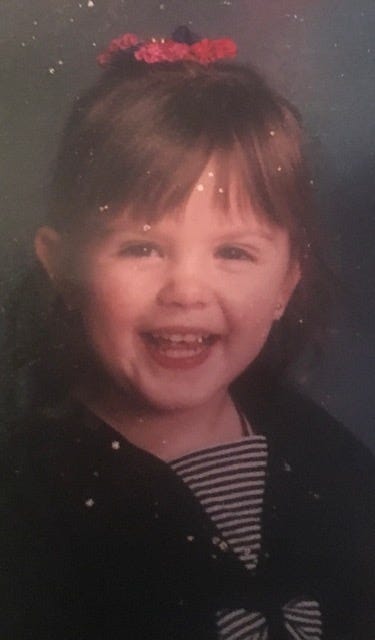

Niamh Haggerty was born in 1998 with a rare cancer in both eyes. Diagnosed at six months, she had an operation to remove her right eye aged four, after gruelling rounds of chemotherapy.

According to Cancer Research UK only 40 to 50 children are born each year with the condition. Niamh, whose family lived in Corby village Stanion when she was a baby, says there was another boy born in neighbouring Weldon village at around the same time with the same rare cancer.

She says:

“My mum noticed she could see through my pupil when the light shined into it, so in January 1999, they took me to Kettering General which said that it was just scar tissue, however they referred us to Leicester.

“Once I was diagnosed I had to go to Birmingham Children’s Hospital and Northampton every three weeks for the first eight months for chemotherapy, plus cryotherapy and laser therapy to freeze any growing tumours.

“Both of my parents had genetic testing to see if they carried the gene and later on my younger sister had the same tests and none of them carry the gene.

“We have known what happened before the show came out, but before the court case was about limbs, so my mum didn’t really think it was anything to do with it.”

Now the family question whether Niamh’s childhood cancer could be linked to the toxic waste clean up.

Danielle Sharp had her first seizure aged seven when she was walking home from Studfall Juniors School. Four days later she had a second. After tests she was diagnosed with hypoparathyroidism, a rare condition that affects the glands in the neck. There are about 150,000 cases worldwide.

Born in 1992 in the Lloyds area of Corby (about two miles from the reclamation sites) she says she was sickly as a young child and would get tired very easily. She had a constant thirst for milk.

She said she has had the rarest symptoms of the condition, and as a child it was rare a fortnight went by without having a seizure. She had low magnesium, vitamin D and calcium.

She has suffered brain damage from her seizures and today she has joint pain and hand cramps which means at times she cannot open them.

She said:

“The problem with the condition is that it’s not very well known. I didn’t know what it was, nor did my mum, because the doctors just spoke in medical jargon. I’ve been in doctors surgery’s where I’ve witnessed doctor’s google my condition.”

Aged 21 she was put under an Oxford based specialist endocrinologist. Genetic testing has found it is not an inherited condition and her own children do not have it.

“He did a genetics test on me and it was not auto-immune. It has not been passed to my kids.

“I am leaning to thinking my illness has been caused by Corby’s toxic waste, because we could not find the reason why I had the condition.”

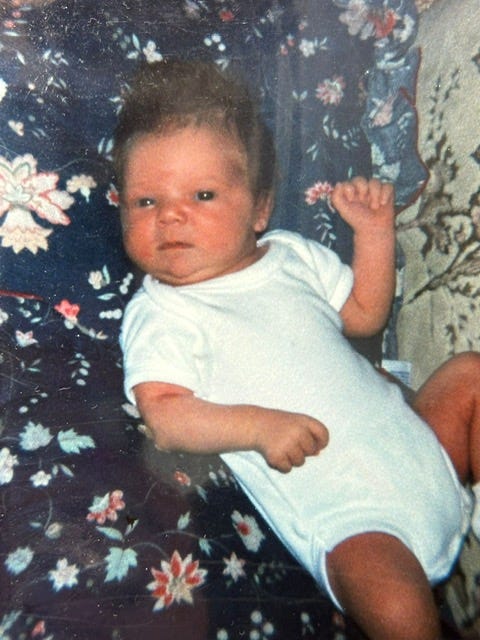

Terry Sandy’s son Ben was born in 1994 at KGH with a rare condition called Hirshsprung’s Disease. This affected his nervous system and intestines and as a newborn he underwent a major operation to remove part of his large intestine. He suffered cardiac arrest during the operation.

At the time Terry and the family were living in Gretton, just a mile from the reclamation site and he worked for Corby Borough Council as a building inspector.

He says:

“Everybody could remember the dust because all the cars were covered in it. I would drive past that site, four times a day, backwards and forwards to work. My ex-wife would drive past if daily. Everybody knew your cars were getting dusted up and just accepted it while the clean up operation is in full swing, you are going to get that.”

He says he had a ‘niggling’ feeling when the original families were fighting their case that his son’s health issues may be connected, and after Toxic Town it has made him have concerns again about the cause of his son’s condition.

“I think potentially it could well be, at that particular time we could not put a finger on why that would happen to him.”

Limb defects

18 families won compensation from Corby Borough Council for their birth defects, but the numbers who were originally part of the case had at one point stood at more than 40.

The legal firm Collins Solicitors whittled down the numbers, as a calculated move to try and make winning the case easier. A link between airborne waste particles and birth defects had not been proven before and so the law firm decided to go forward with a cluster.

That means that some original families did not get compensation, or justice. Since Toxic Town was aired more families with birth defects have come forward.

Adam Stanford was born at KGH in July 1991 with deformities of both feet. His dad used to fly model airplanes on land close to the clean up site (on a site which is now part of Rockingham Speedway) and his mum would visit the site while pregnant with Adam. The family think this is where they could have been exposed to the toxic waste particles.

As a baby he had leg braces, then wore special boots until the age of five and he had therapy until 12 months. He can only walk at a two mile an hour pace, has never been able to run and is in pain every day.

As a child he grew up on the Lincoln area of Corby, a housing estate, which then, as now, was plagued by crime and his club feet meant he was a target.

“I used to get into fights because I grew up on Canada Square, people remember what that place was like. I couldn’t run. People would start on me. What am I going to do? I can’t waddle away at two mile an hour. I got jumped loads of times when I was a teenager.”

He was part of the original legal action before solicitor Des Collins reduced the claimant numbers.

He said:

“Recently I have become mad, because it is a loss. I am from a poor town where a life changing amount of money would have made a big difference to me. I was just kind of ignored while the rest [of the claimants] went through.”

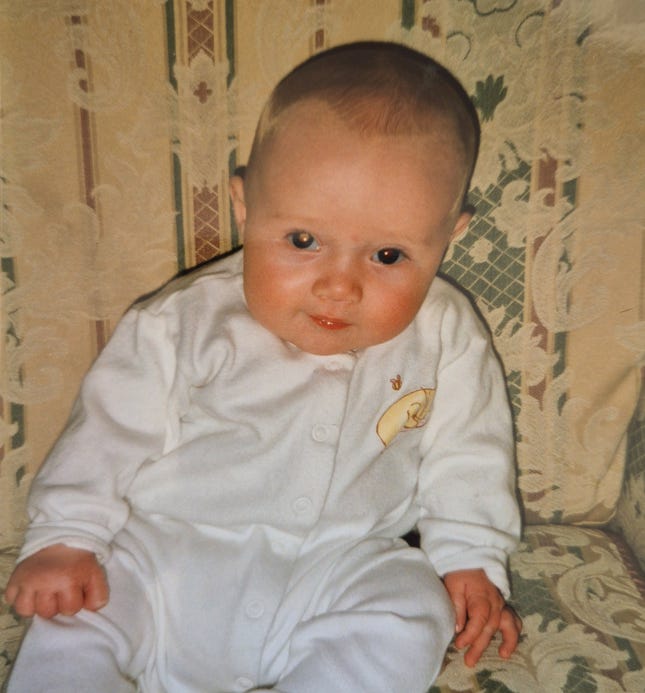

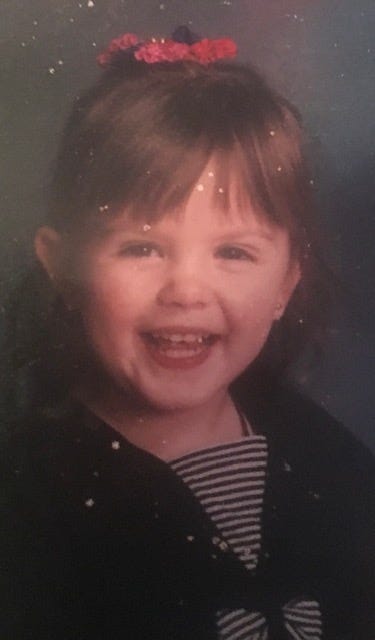

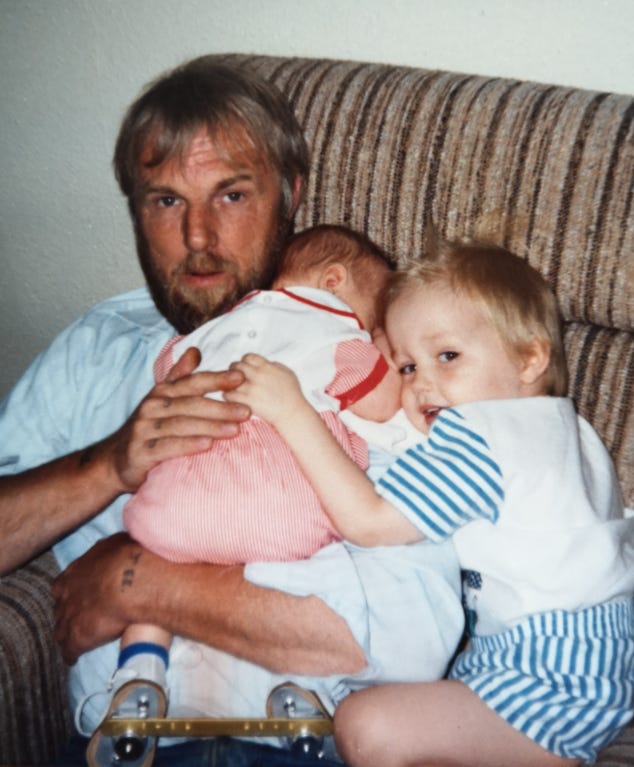

Twins Emily and Shannon Pickaver were born prematurely at Kettering General in February 2001, at 28 weeks, Emily weighing less than two pounds and her sister slightly heavier. Both were born with congenital talipes equinovarus, commonly known as club feet, where the feet are twisted inwards. A family member overheard a nurse caring for the babies at the hospital say ‘there’s another one from Corby’.

Today aged just 24 and after years of operations and procedures Emily, who now lives in the South West with her mum and sister, is considering having an amputation.

She says:

“I have never known a day without pain. I have to take strong daily painkillers and have severe tiredness. When we watched Toxic Town, it just clicked. The programme really upset us and we would like to know if our health problems have been caused by toxic waste.”

The twins mum Jackie was working at the former Nielsens Clearing House coupon depot on the Weldon Industrial estate when she was pregnant. The reclamation trucks with their open backs would pass daily. She says at the time of their birth no reason was put forward for their conditions and after their premature birth ‘everything was just a whirlwind’. Both girls underwent procedures, having their legs broken and reset, wearing corrective bars on their feet and suffering splints that made their ankles bleed.

Jackie says:

“It was traumatic for us all. We just got by day by day. Today their bones are a mess.”

Heart conditions

Jack Perrin was born in 1997 with a hole in his heart and has undergone three operations since birth. He will need to have follow up ops every ten to 15 years.

His dad Alan worked for the contractor Weldon Plant, the primary firm that undertook the cleanup, as a groundworker on the Asda supermarket scheme (on the site of the former blast furnace).

On one occasion an unknown substance on his work trousers melted a hole in it overnight.

Jack says his family have often wondered if there could be a link between his heart problems and the toxic waste.

“There seems to be a large demographic in Corby of people with heart defects. Maybe I’m just connecting the dots - but I think there is something more to it.”

“It has not stopped me from doing anything, but it has always played on my mind. We talk about the physical aspects but I feel like the mental aspects are more damning.”

Taylor Stratford grew up on Stephenson Way, just behind the former steelworks site. Born in 1994. She has Wollf-Parkinson-White syndrome and her heart has two pathways.

It wasn’t until she was in her mid 20s that she was diagnosed after suffering palpitations. She has a device in her chest that sends data back to the hospital and has undergone surgery. She also has scoliosis, arthritis, missing cartilage in her legs and was born with an extra finger.

She said:

“I watched the BBC documentary [which aired in 2020] and I was saying to my mum ‘Does that not make you think?’ We literally lived at the back of the steelworks site.”

What is happening now?

In recent weeks the campaign to find out whether the legacy of Corby’s toxic waste has had a much bigger health impact than was originally thought, has been gathering pace.

Two mothers from the original case, Tracey Taylor and Maggie Mahon, whose person stories featured in Toxic Town series, have been leading efforts to bring others forward and are calling for a full investigation of what happened.

This month they gathered 30 families at a Corby social club and heard people’s stories. It was reported on the national ITV news.

Des Collins, the original solicitor, has joined the families in calling for a public inquiry and in the past two weeks Corby councillor Mark Pengelly has taken the issue back into the council chamber.

He has told the senior officers and the director of public health Jane Bethea that they need to listen to the families and start to investigate, warning of what happened two decades ago when the local authority dismissed the families’ concerns after the birth defects cluster was first exposed in the Sunday Times.

A group of families with children born in the recent decade who have cancer have also met with the public health director and asked her to look into local cancer rates.

Tracey Taylor, whose daughter Shelby died days after birth, says she is now more hopeful the called for public inquiry will happen.

She said:

“We just want to help people get justice.

“All the people say the same thing, they feel guilty and can’t move on with their lives. We’re helping them and are helpful we can move this forward.”

A spokesperson for North Northamptonshire Council said:

“The Public Health team have conducted an analysis of hospital data from the past ten years. This assessed cancer data for each district of North Northamptonshire, and for small areas within these. The small areas that were compared are known as lower super output areas (‘LSOAs’). LSOAs are used in the census and usually have between 1,000 and 3,000 residents.

“The team used the hospital data to infer the rate of children living with cancer per number of children living in the districts and LSOAs. This analysis is almost complete, and we will be discussing the findings initially with the group that made the request.”

Many thanks to the families for sharing their stories. If you think you could have been affected by the issues in this article, please contact Sarah Ward on the details below.

Tracey Taylor also has created an online form that families who think they could be affected, can fill in.

Brilliant piece of work by NNJ and everyone as momentum has gathered over the past couple of years, thank you to the second wave of pioneers willing and able to stand up and speak out including Alison, and Tracey who brought people together.

Congratulations to the NNJ team once again for an excellent and timely piece of community journalism. Make sure it is seen as widely as possible by telling everyone you know about it and if you can, please subscribe to the site so essential work like this can continue.